Recently, the CDC reported that in 2021, 42% of students felt persistently sad or hopeless and 29% experienced poor mental health with 22% of them seriously considering suicide, and 10% attempting suicide. This was more pronounced in girls; nearly 60% of teenage girls reported feeling persistent sadness or hopelessness. The question many have asked is what is causing this crisis.

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, who co-wrote the book “The Coddling of the American Mind” on which they detail how students, since 2013, were “saying that an unorthodox speaker on campus would cause severe harm to vulnerable students (catastrophizing); they were using their emotions as proof that a text should be removed from a syllabus (emotional reasoning).” Lukianoff hypothesized that if colleges supported the use of these cognitive distortions, rather than teaching students skills of critical thinking, then this could cause students to become depressed.

Haidt has written on Substack detailed research essay titled “Why the Mental Health of Liberal Girls Sank First and Fastest” supporting the hypothesis that political identification has affected their mental state.

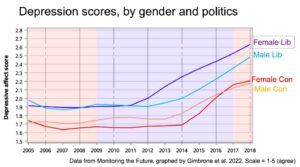

In recent weeks—since the publication of the CDC’s report on the high and rising rates of depression and anxiety among teens—there has been a lot of attention to a different study that shows the gender-by-politics interaction: Gimbrone, Bates, Prins, & Keyes (2022), titled: “The politics of depression: Diverging trends in internalizing symptoms among US adolescents by political beliefs.” Gimbrone et al. examined trends in the Monitoring the Future dataset, which is the only major US survey of adolescents that asks high school students (seniors) to self-identify as liberal or conservative (using a 5-point scale). The survey asks four items about mood/depression. 1 Gimbrone et al. found that prior to 2012 there were no sex differences and only a small difference between liberals and conservatives. But beginning in 2012, the liberal girls began to rise, and they rose the most. The other three groups followed suit, although none rose as much, in absolute terms, as did the liberal girls (who rose .73 points since 2010, on a 5-point scale where the standard deviation is .89).

Figure 2. Data from Monitoring the Future, graphed by Gimbrone et al. (2022). The scale runs from 1 (minimum) to 5 (maximum).

The authors of the study try to explain the fact that liberals rise first and most in terms of the terrible things that conservatives were doing during Obama’s second term, e.g., “Liberal adolescents may have therefore experienced alienation within a growing conservative political climate such that their mental health suffered in comparison to that of their conservative peers whose hegemonic views were flourishing.”

But other progressive journalists have different opinions. Jill Filipovic, of the NY Times, has said that “progressive institutional leaders have specifically taught young progressives that catastrophizing is a good way to get what they want.” A quoted passage from an essay by Filipovich expresses the same concerns that Lukianoff has:

I am increasingly convinced that there are tremendously negative long-term consequences, especially to young people, coming from this reliance on the language of harm and accusations that things one finds offensive are “deeply problematic” or even violent. Just about everything researchers understand about resilience and mental well-being suggests that people who feel like they are the chief architects of their own life — to mix metaphors, that they captain their own ship, not that they are simply being tossed around by an uncontrollable ocean — are vastly better off than people whose default position is victimization, hurt, and a sense that life simply happens to them and they have no control over their response.

Haidt’s essay goes on to show data that supports Filipovic’s “captain their own ship” concern and Lukianoff’s disempowerment concern:

Gen Z has become more external in its locus of control, and Gen Z liberals (of both sexes) have become more self-derogating. They are more likely to agree that they “can’t do anything right.” Furthermore, most of the young people in the progressive institutions that Filipovic mentioned are women, and that has become even more true since 2014 when, according to Gallup data, young women began to move to the left while young men did not move either way. As Gen Z women became more progressive and more involved in political activism in the 2010s, it seems to have changed them psychologically. It wasn’t just that their locus of control shifted toward external—that happened to all subsets of Gen Z. Rather, young liberals (including young men) seem to have taken into themselves the specific depressive cognitions and distorted ways of thinking.

Haidt then explores possible causes that may have influenced the change in these young people. He quotes Megan Phelp-Roper who has interviewed several experts on the issue; they “all pointed to Tumblr as the main petri dish in which nascent ideas of identity, fragility, language, harm, and victimhood evolved and intermixed.”

Haidt also quotes Angela Nagel (author of Kill All Normies) who described the culture that emerged among young activists on Tumblr, especially around gender identity, in this way:

There was a culture that was encouraged on Tumblr, which was to be able to describe your unique non-normative self… And that’s to some extent a feature of modern society anyway. But it was taken to such an extreme that people began to describe this as the snowflake [referring to the idea that each snowflake is unique], the person who constructs a totally kind of boutique identity for themselves, and then guards that identity in a very, very sensitive way and reacts in an enraged way when anyone does not respect the uniqueness of their identity.

Haidt recommends two policy changes that should be implemented:

1) Universities and other schools should stop all programs that teach children and adolescents to embrace harmful, depressogenic cognitive distortions. These programs range from diversity training to trigger warnings, and include initiatives to remove words and phrases that are said to be “harmful.” Haidt claims that “these very programs are causing liberal students to feel disempowered, as if they are floating in a sea of harmful words and people when, in reality, they are living in some of the most welcoming and safe environments ever created.”

2) The US Congress should raise the age of “internet adulthood” from 13 to 16 or 18. Haidt points out that “[t]he evidence is abundant that social media is a major cause of the epidemic, and perhaps the major cause. It’s time we started treating social media and other apps designed for “engagement” (i.e., addiction) like alcohol, tobacco, and gambling, or, because they can harm society as well as their users, perhaps like automobiles and firearms.” He adds: “It’s not enough to find more money for mental health services, although that is sorely needed. In addition, we must shut down the conveyer belt so that today’s toddlers will not suffer the same fate in twelve years. Congress should set a reasonable minimum age for minors to sign contracts and open accounts without explicit parental consent, and the age needs to be after teens have progressed most of the way through puberty.”

I agree with Haidt something must be done. His recommendations are sensible, but I am afraid the institutions we hope will recognize they are part of the problem will simply ignore them as a conservative attack.

But there is more than legislation. Our culture has no reverence or tolerance for suffering of any kind. As a result, some people believe in a utopian view that everybody should get the same outcomes. Many argue that suffering leads to growth. Most saints in the history of the world have overcome suffering.

If God sends you many sufferings, it is a sign that He has great plans for you and certainly wants to make you a saint.

St. Ignatius Loyola

The push to eradicate suffering has created unforeseen consequences and led to the growing depression and hopelessness among teenage girls and the “crisis of men,” who lag behind women in education and the workplace.

Katherine Boyle has written an insightful essay in Substack, “Get Serious: About Suffering”. She says:

Though we may not realize it, nearly all of our modern cultural debates and ailments stem from the contemporary belief that suffering is not a natural or essential part of the human condition. The war on suffering has not only robbed us of resilience; it has sold us a mirage that is making us miserable.

It is not a coincidence that the modern campaign to eradicate suffering commenced just as religiosity in general and Christianity, in particular, began to decline at a rapid pace in America. There is no religion that doesn’t embrace suffering as integral to its teaching. Christianity deified it, with adherents wearing a symbol of torture as a symbol of their belief. Buddhism declares suffering its First Noble Truth. Stoicism acknowledges suffering while rejecting its dominance, and modern philosophers such as Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl wrote, “If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering.”

Some people call any kind of suffering oppression. Consequently, we don’t want anyone to lose; we are adamantly trying to eradicate suffering, even the mildest form of suffering—once referred to as adversity. The question is, why aren’t we happier?

As Boyle alludes, the abandonment of religion and morality has left many young people thinking that it is acceptable to do and act as they please. This lie has been sold as a way to reduce “judging other people” and practice tolerance.

But removing religion as a moral framework has left our youth unmoored without an anchor and a source of hope. Several studies (see here, here, and here) have shown evidence that supports the idea that increased religiosity is associated with better mental health demonstrating that religiosity has a significant protective factor and carries many positive effects against depression.

As parents, teachers, or anyone dealing with the youth, we would be remiss to dismiss the potential beneficial effect of religiosity in our youth.

three teenagers praying in a church